🪑 Our workspaces and us

The cubicle you hate was designed to set you free and what that means for software.

Every Friday, we send an email that details what we released in Kosmik during the week, what we’re working on next week, and a little note of anything that’s been top of mind.

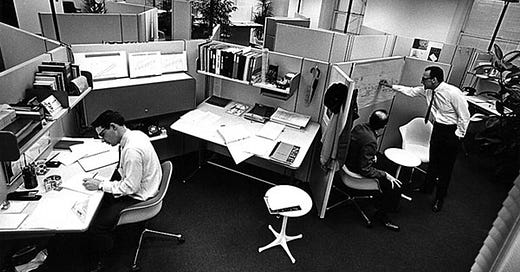

For pictures of the Action Office being designed in the 60s— go here!

In 1968 Robert Propst wrote a small book, The Office (not to be confused with anything Michael Scott-related). In that book, he highlights one fact we now know to be true: the 20th century is the first century where change is the only constant thing.

In the 20th century everything is going upwards and to the right (literally 📈): the number of cars produced, the number of people on the planet, the volume of information we create.

Propst warned of the coming “Paperpocalypse” that would soon devastate any company whose main business is knowledge. In any company, the number of projects to track, of reports to write, phone calls to make was exploding. The computer already existed but only in a distant room filed with cold air and a few discreet people manning the mostly text-based, green-on-black screens. To keep things under control, Propst devised a new kind of office floor plan, which he developed with George Nelson at Hermann Miller.

The office was ripe for change and had been for at least a decade. The open floor plan offices were becoming bigger and bigger as the post-war period created a period of abundance and growth for most western countries.

Burolandschaft, the office as a landscape

This period gave two German designers the idea of overhauling the classical (and dull) bullpen. Their creation was titled burolandschaft or “office landscape”, a new way to organise open plan offices with irregular placements of furnitures to give the room a more organic feel.

This pattern had also been designed to focus on the individual and its place within the organisation. Even if each table was the same and even if the floor plan was still basically an open plan, the uniqueness of each corner of the office gave every worker a table “of its own”. Finally, burolandschaft was supposed to be a more egalitarian environment where executives and staff members would be collocated together, working side-by-side. the idea was to allow for easier communication between individuals and entities within the company.

Robert Propst became a strong advocate of the burolandschaft approach but he nonetheless flagged some issues. Those issues were already part of the classic bullpen or open plan office but they were heightened by the office landscape since the whole company was supposed to inhabit the layout. Propst thought that the design could be improved by focusing on its most problematic aspects:

Noisy

Lack of privacy

Cannot be personalised

Beyond these issues (that are still with us today), Propst highlighted the stillness of the worker in a classical open plan office setting. He insisted that people needed to move around, sometimes to refocus on the task at hand. Having offices in a completely open plan also meant that nothing could be left on the tables at night. “Displaying” items, documents, magazines and notes became a quest for Propst who even went as far as to write: “what is out of sight is out of mind”.

As you’ll see in a moment, these issues are shared in large parts by our current digital work environment.

The Action Office — a facility based on change

The Action Office 1 or AO1 was introduced in 1964. It revolved around an array of dividers that were to be installed at a 120° angle to create a honeycomb like structure. That structure created a semi-open office plan where workers would have a semi-private office of their own. The office could be configured with shelves, a telephone “station”, a roll-top table to leave papers in a specific arrangement overnight and tables.

Here’s how the AO1 was supposed to look like in real life:

The blank spaces between the honeycombs structures creates hallways to move between the offices. Workers have privacy yet easy access to their colleagues, private conversations are possible, serendipitous meetings fostered.

The Action Office did not really take off with its first version but it gradually became a best seller in its later incarnation. The principles of Propst were unfortunately twisted in the following years. Managers and bosses around the world realized that by arranging the dividers not at a 120° angle, but a 90°, angle they could cram many many more workers into the same space.

The unfortunate cubicle was born, by accident and Robert Propst became know as the man who invited it.

The problems that Propst tried to solve with furniture and clever filing systems (the action office came complete with a specific set of manilla folders with a color coding system), we now have to solve them digitally.

We are facing the same issues with modern SaaS software and computers.

Personal, interpersonal, overwhelming

Our computers are very powerful and capable of dealing with an inordinate amount of data — but they’re held back by an antiquated file system, inadapted metaphor to manipulate said files and a stretched browser that is trying to cram an OS on top of the OS without having access to some of the OS’ most precious resources.

We are running in circles and we can do better!

Those problems have been with us since the early 1990’s and both Apple, Microsoft, NeXT, Be, Sun and countless other firms tried to solve them. As is often the case with such user facing issues, Steve Jobs had a great way to describe the problem in one of the NeXT demos he recorded. This one, titled “Interpersonal computing” seems prescient. I’m copy-pasting the most accurate passage from an article by M.G.Siegler over at GV:

“We also can’t change our geographic organization very fast. As a matter of fact, even slower than the management one — we can’t be moving people around the country every week. But we can change an electronic organization — *snaps* — like that. And what’s starting to happen is as we start to link these computers together with sophisticated networks and great user interfaces, we’re starting to be able to create clusters of people working on a common task — literally in 15 minutes worth of set up. And these 15 people can work together extremely efficienctly no matter where they are geographically, and no matter who they work for hierarchically. And these organizations can live for as long as they’re needed and then vanish. And we’re finding that we can reorganize our companies electronically very rapidly. And that’s the only type of organization that can begin to keep pace with the changing business conditions.”

This was said in 1993 when the web was in its infancy and broadband networks a very recent reality for a very small number of people. You can watch the original video here, it’s a really interesting glimpse into the future of computing of 1993.

In the early 80’s the goal was to put a computer on every desk; by the mid 1990’s the desk was in the computer; by the mid 2000’s every computer could be on any computer.

The fundamental metaphors of the personal computer have not changed. It’s as if we’re all still working in 19th century in bullpens, but with 10 telephones on each desk, yelling to cover the ambient noise. This is what it feels:

Slack

Outlook

Chrome

Figma

Discord

Whatsapp

Notion

Google Doc

Excel

PDF reader

We’re getting overwhelmed. We need a digital action office — a software based on change.

A software based on change.

The answer to this problem has always been to let the UIs cohabitate and to create integrations within the applications.

In 1991, one of the highlighted features of “System 7” was the ability for apps to “publish” and “subscribe” to one another. Create a spreadsheet in Excel, subscribe to it in a package that can generate a graph (yes those were two different apps) and then publish and subscribe to both in hypercard to create slides (but interactive, see interactive information).

We’ll see 3 ways to approach this problem in the coming years;

A continuation of the current way of creating integrations with API calls and scripting.

The delegation of that task to agents that will create a new layer of abstraction (even going as far in some case as completely obfuscating the user interface of certain products)

The emergence of multimedia (Canvas based or not) polymorphous applications capable of both scrapping the web, legacy files and interconnecting them together

Kosmik is in the third category, but as we see from apps and SDKs like tldraw those approaches will probably converge to create a new layer for users to interact and hopefully to interact together.

AI will provide the integrations (maybe, probably, we’ll see) and do the data scraping, gathering and in some cases combining but where will the output be placed?

In a file to store within a hierarchical tree?

Removed from the collaborative layer that is day after day gaining ground on our computers?

In an app, removed from the other relevant documents needed for the project?

Or in a new, digital third place that will be able to store and “read” PDF, files, websites, Figma files, Notion documents and mix them together in one coherent environment where it becomes possible to glue part of them together in an integrated way?

We have left the personal computer, its comforting coherence and consistency. What we’ve gained in this process is the interpersonal layer. The constant possibility of another presence in the file, the immediate input of our coworkers. We can probably have our cake and eat it too now by interrogating each metaphor we use currently and by building a new layer for integrated software.

What we’ve been working on this week

We pushed Kosmik 2.9 — here’s what you’ll find in new release:

New features 🚀

You can configure the appearance of Kosmik in user settings! You can now choose wether you want Kosmik UI to have the same colour theme as your OS or manually set light/dark mode.

We’ve corrected numerous bugs in Kosmik 2.9 and we’ve finally finished our work on the Asian infrastructure to allow users from any country to sign-up and use Kosmik as efficiently as in Europe or in America.

Minor improvements ✨

Keyboard shortcut to create a new universe:

On MacOS: Cmd+U

On WindowsOS: CTRL+U

Images are displayed in a higher resolution in the side panel (to open the side panel, click on an image and press “space”).

What we’re working on

Other than continuing our quest to scale our infrastructure and make Kosmik more standard, easier to use and integrate within your existing workflow, we’re working on arrows! Coming very soon to Kosmik 2.10.

As always, please let us know what you think of the new release!

Until next week —

Paul.